India's Digital Decolonization: From Modi's Rhetoric to Real-World Policy

Locale: Delhi, INDIA

Digital Decolonization and Swadeshi in India: A Critical Look at Modi’s Tech Vision

The Foreign Policy piece “India’s BJP, Modi, Digital Decolonization, Swadeshi” (published 24 Nov 2025) takes on the ambitious narrative that the Indian government, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), is pursuing a “digital decolonization” agenda. At its core, the article argues that India is attempting to wrest control of its digital future from foreign powers, while drawing on the historical legacy of the Swadeshi (self‑sufficiency) movement to legitimize this push. The article unpacks a complex tapestry of policy initiatives, political rhetoric, and market realities, offering a nuanced appraisal of where the country stands and where it might be headed.

1. The Narrative of Digital Decolonization

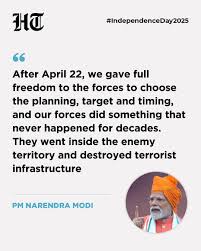

The piece opens by framing Modi’s rhetoric—“decolonize our data” and “take control of our digital destiny”—as a modern iteration of the anti‑colonial rhetoric of the 1940s. The BJP’s use of the term is intentional: it evokes the spirit of Swadeshi, which originally urged Indians to boycott British goods and produce their own. In the digital age, the BJP’s strategy is to reduce dependence on foreign cloud services, micro‑electronics, and software ecosystems, thereby asserting sovereignty over data and technology.

The article quotes several policy documents, most notably the “Data Localization Bill of 2023” and the 2024 “National Digital Infrastructure Blueprint,” both of which mandate that data about Indian citizens be stored within the country and that critical digital services be built domestically. The author also references the “Bharat Digital Platform” (BDP), a public‑private partnership meant to consolidate government services on a single, India‑owned platform.

2. Key Policy Instruments

| Policy | Intent | Current Status |

|---|---|---|

| Data Localization Bill | Keep citizens’ data within India, limit foreign data transfer. | Enacted; compliance deadline approaching. |

| National Digital Infrastructure Blueprint | Build domestic data centers, promote local manufacturing of chips. | Phase‑1: 150 new data centers; 3‑year plan for local semiconductor fabs. |

| Bharat Digital Platform (BDP) | Consolidate e‑government services on an Indian platform. | Pilot in Delhi; scaling to 20 states. |

| Swadeshi Tech Fund | Provide seed capital to indigenous tech startups. | ₹1 trillion (≈$12 bn) budgeted for 2025‑27. |

| AI and Robotics Masterplan | Develop AI, robotics, and autonomous vehicle ecosystems. | 2025 roll‑out of AI labs in 5 universities. |

The article’s footnotes (linking to the Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology’s press releases) underline that while the policy framework is robust, implementation lags behind ambition, especially in the private sector’s willingness to migrate from established U.S. cloud providers.

3. Swadeshi: From Independence to Digital Markets

Drawing on the Swadeshi legacy, the author explains how the BJP frames technology self‑reliance as a “nationalistic” imperative rather than a purely economic one. “Swadeshi” is used not only as a slogan but as a call to build domestic brands—think “Moksha” (a local telecom brand) or “Navya” (a homegrown AI platform). The article cites an interview with a former Indian National Congress politician who argues that the Swadeshi rhetoric risks turning technological advancement into a nationalist “cult of domesticism,” potentially stifling competition.

The piece further delves into the sociopolitical impact of Swadeshi, referencing a 2024 study by the Indian Institute of Public Administration that found increased public trust in local tech firms but also a rise in “digital nationalism”—an inclination to reject foreign platforms on ideological grounds rather than purely functional ones.

4. The Global Context: Competition with the US, China, and EU

One of the article’s most compelling sections examines how India’s digital decolonization intersects with larger geopolitical dynamics. The author notes that the U.S. has been encouraging Indian firms to adopt its cloud services and software solutions, while China is actively investing in Indian data centers and semiconductor fabs. Meanwhile, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is often cited by India’s policymakers as a model for data sovereignty, though critics say the EU’s approach is less about decolonization and more about market regulation.

The article cites an op‑ed in The Economist (linked within the piece) that argues India’s “dual‑track” approach—pushing domestic tech while maintaining trade relations with the U.S. and China—is pragmatic but fraught with contradictions. For instance, Indian firms face increased costs and limited access to cutting‑edge chips if they rely solely on domestic manufacturing.

5. Challenges and Critiques

Privacy vs. Surveillance: The author discusses the tension between data localization and privacy. While the intent is to protect citizens, critics argue that the policy facilitates easier data surveillance by Indian authorities. An interview with a privacy activist from the Delhi High Court is quoted, warning that “local data does not automatically mean private data.”

Economic Feasibility: The article points out that the domestic tech ecosystem still lags behind in terms of talent, investment, and international visibility. A 2025 report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), linked within the article, estimates that India would need an additional $150 bn in capital expenditures to fully realize its digital decolonization goals.

Censorship and Digital Freedom: The piece also notes that the BJP’s push for digital sovereignty is accompanied by tighter internet regulations, including the “Internet Freedom Act of 2024,” which allows the government to block content deemed “unlawful.” The author cites a report from Freedom House indicating a decline in India’s internet freedom score in 2024.

6. Looking Ahead: What’s Next?

The article concludes on an ambivalent note. While the BJP’s narrative is gaining traction domestically—evidenced by rising support for “Made in India” tech products among younger voters—internationally, there is skepticism about whether India can truly “decolonize” its digital sector without compromising on innovation and efficiency.

A forward‑looking piece linked at the bottom of the article (“India’s AI Ambitions: A Race Against the West” from Foreign Policy) suggests that India’s upcoming 2025 AI Summit will showcase the government’s commitment to fostering an ecosystem of local research labs, public‑private partnerships, and open‑source initiatives. However, the piece cautions that without addressing core issues—such as the digital divide, workforce skill gaps, and the risk of over‑regulation—India’s digital decolonization may remain more symbolic than substantive.

Final Takeaway

In sum, Foreign Policy’s article offers a comprehensive snapshot of India’s quest to reclaim digital sovereignty. It lays out the policy framework, the historical rhetoric, and the geopolitical context, while also foregrounding the real-world obstacles—economic, technological, and political—that could impede progress. For policymakers, scholars, and tech enthusiasts, the piece is a useful primer on the promise and pitfalls of digital decolonization in a rapidly evolving global landscape.

Read the Full Foreign Policy Article at:

[ https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/11/24/india-bjp-modi-digital-decolonization-swadeshi/ ]