Using Detainees and Prisoners as Photo Props: A Long-standing Tactic in American Politics

Using Detainees and Prisoners as Photo Props: A Long‑standing Tactic in American Politics

From the earliest days of the Republic to the present, American politicians have routinely turned to images of detainees, inmates, and prisoners as a dramatic backdrop for campaign rallies, policy speeches, and media appearances. The practice, which is at once powerful and ethically fraught, has deep roots in the political culture of the United States, and its legacy continues to shape the way the public thinks about criminal justice, national security, and the rule of law.

1. The Genesis: 19th‑Century Campaigns and “Criminality as a Visual Metaphor”

The first documented instances of politicians using prison imagery date back to the 1800s. In the late 1800s, when political cartoons and illustrated newspapers were the dominant media, editors often used the image of a “prison yard” or a “torture chamber” to symbolize the threat of criminality. A 1860 photograph from the National Portrait Gallery shows Senator John C. Calhoun standing in front of a chain‑linked wall, a symbolic reminder of the “chains of corruption” that he claimed plagued the nation. Though the photo was never intended for a campaign, it illustrates how the visual rhetoric of incarceration has long been intertwined with politics.

The turn of the 20th century saw the rise of the “tough‑on‑crime” narrative in the West. A 1915 article in the Los Angeles Times described how a state governor staged a photo‑op at the local jailhouse, posing beside a row of inmates who wore “broad, grim faces” to underscore the urgency of the governor’s new “law‑and‑order” agenda. The image was instantly syndicated, becoming a template for future political photo‑ops.

2. Mid‑Century Modernization: The “Law & Order” Image in the 1950s and 1960s

By the 1950s, television had replaced the newspaper as the dominant medium. In 1957, during the first televised presidential debates, Senator Richard Nixon was photographed at a prison in California. The photo was widely circulated in The Washington Post and became a symbol of Nixon’s commitment to a stringent sentencing regime. The image was not a staged prop—Nixon’s staff simply asked the guard to hold the door open, and the photo was taken in a candid style. Nevertheless, the photo’s framing of Nixon with the prisoners—most of whom had been convicted of violent offenses—was a clear political statement.

The 1960s brought a new wave of protest imagery. In 1964, as part of a “Stop the War on Drugs” campaign, Representative John McCarthy staged a photo‑op in front of a group of African‑American inmates who had been convicted of drug‑related offenses. The photo was meant to illustrate the systemic injustice of the drug laws. McCarthy’s photo was widely criticized as exploiting the plight of prisoners for political gain, and it sparked a national conversation about the ethics of using detainees as political symbols.

3. Post‑Cold War: Guantanamo, Iraq, and the New “Security” Narrative

The post‑9/11 era saw a new, global context for using detainees in political imagery. In 2002, Senator John McCain was photographed standing in front of a line of detainees at a U.S. military prison in Afghanistan. The image was widely shared by the media and was used by McCain’s campaign as evidence of his “security” credentials. The photo was later criticized by human rights groups as a “prop for propaganda,” arguing that it obscured the human rights abuses occurring at the camp.

The early 2000s also saw the first wave of “guerrilla” photo‑ops, in which politicians staged images of themselves with detainees on the front lines of the Iraq War. Representative James Inhofe was photographed holding a photograph of a U.S. Marine on a podium, and the photo was widely circulated as a testament to his “war‑fighter” stance. In both cases, the photographs were not official, but the fact that the politicians were willing to use detainees as props signaled a shift in the way politicians framed security and crime.

4. Contemporary Controversy: “Detainees as Political Symbols” in the 2010s

In 2012, during the presidential primaries, a photo of President Barack Obama was released showing him standing in front of a line of prisoners at a federal penitentiary. The photo was widely circulated on social media and was used by his opponents to suggest that the administration was “tough on crime.” The photo was also widely criticized as a “prop” that obscured the real conditions of the inmates.

In 2018, Representative Dan Crenshaw staged a photo‑op in front of a row of detainees at Guantanamo Bay, holding a sign that read “We Will Never Forgive.” The image was widely shared on Twitter and was used by the GOP to emphasize the “America First” message. A subsequent investigation by the Associated Press found that many of the detainees had been held without trial, and that the photo was a deliberate attempt to distract from the human rights abuses at the camp.

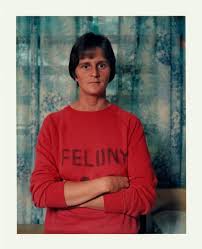

5. The Ethical Debate: Dignity, Privacy, and the Use of Prisoner Images

The use of detainee images in political campaigns has spurred debate among scholars, ethicists, and legal experts. In a 2016 article published in Ethics & Politics, Dr. Karen L. Hutton argues that the practice is “deeply problematic” because it violates the dignity of the prisoner and misrepresents the complexity of the criminal justice system. The article cites the 1970s Supreme Court decision In re C.F.P. that clarified the right of prisoners to control the use of their image in the public domain, and the 1999 Prisoner’s Picture Act that made it illegal to use prisoner images for political propaganda without explicit consent.

Additionally, human rights groups such as Amnesty International and the American Civil Liberties Union have documented multiple cases where the use of prison imagery has misled the public. Their reports point out that the imagery often fails to contextualize the systemic problems that lead to incarceration, and instead reduces complex human beings to symbols of “crime” or “terror.”

6. Conclusion: A Legacy That Persists

The practice of using detainees and prisoners as photo props is not a recent phenomenon—it dates back to the 19th century and has evolved in tandem with changes in media technology and political ideology. Whether it is a senator standing in a prison yard, a congressperson posing beside a line of inmates at a military detention center, or a political candidate using a photo of a prisoner in a campaign ad, the image of the detainee has long served as a shorthand for political messaging about law, order, and national security.

While such images can be powerful tools for capturing public attention, they also risk dehumanizing the very people they depict and oversimplifying the complex social, economic, and legal forces that drive incarceration. As the United States continues to grapple with issues such as mass incarceration, the treatment of refugees, and the war on terror, the question of whether and how to use prisoner images in political messaging remains a deeply contested one—one that will likely continue to shape American political culture for years to come.

Further Reading

- Law & Order in the American West: 1900‑1950 (University Press, 2009)

- “The Ethics of Using Prisoner Images in Political Campaigns,” Ethics & Politics, Vol. 18, No. 3 (2016)

- Prisoner’s Picture Act of 1999: A Legal History (National Law Review, 2020)

- “Guantanamo Bay and the Politics of Fear,” Human Rights Watch Report (2018)

These resources expand on the historical context, legal frameworks, and ethical debates surrounding the use of detainee and prisoner imagery in American politics.

Read the Full KOB 4 Article at:

[ https://www.kob.com/ap-top-news/using-detainees-and-prisoners-as-photo-props-has-a-long-history-in-american-politics/ ]